How to manage your stress levels

by befriending your nervous system

Stress is part of life, part of being human; unavoidable unless you’re hiding away, not really living at all. Arming yourself with knowledge about what happens physiologically at those times is powerful stuff and can help you respond differently in the moment when you are feeling stressed.

What I’m talking about here is our survival responses, governed by our autonomic nervous system

Stress isn’t just something in our minds. It’s a whole body thing. Our autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a huge part in how we feel in day to day life and yet is talked about fairly infrequently. When we are stressed our autonomic nervous system has shifted into a state of mobilisation (‘Fight/ Flight’).

Here, I aim to provide an overview of three ANS survival states and their impact on our experience.

Why do you need to know this?

Because knowledge is power. Because every single one of us has an autonomic nervous system and understanding its unconscious nature can bring a more compassionate perspective towards yourself and others, particularly in challenging moments when you are feeling stressed.

Also because you can learn to calm your nervous system and in so doing, become less reactive to stressors. Change is absolutely possible!

The benefits of getting to know yourself in this way are huge.

On the following pages you will find an introduction, a bit of science (skip this part if you’d prefer), plus a link to worksheets to help you map your own experience and bring about change.

Introducing your autonomic nervous system (ANS)

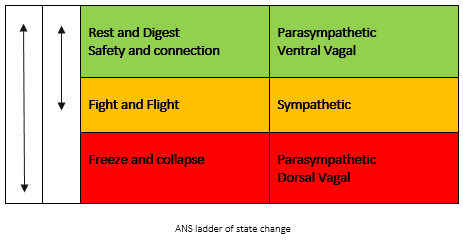

The keyword here is autonomic. By that, we mean unconscious and involuntary. This part of our nervous system is responsible for unconscious processes such as maintaining internal homeostasis and responding to changes in the environment. It is also responsible for activating three survival states, commonly known as 1) Rest/ Digest 2) Fight/ Flight and 3) Collapse/ Freeze.

The basic science

The ANS is a complex system comprised of two main branches: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system could be described as ‘the accelerator’ and is associated with the body’s fight or flight response.

The parasympathetic nervous system could be described as ‘the brake’ and is divided into 2 further branches: the ventral vagal pathway – associated with the body’s rest & digest response and the dorsal vagal pathway – associated with the body’s collapse/ freeze response.

Vagal means ‘relating to the vagus nerve’: the nerve (or bundle of nerves) that make up the parasympathetic nervous system.

When triggered, we experience these states in a set order, shown in the table below, as if climbing up and down a ladder:

A couple of interesting things here…

- You will notice that the freeze/ collapse response lies beyond fight/ flight. Imagine playing dead, or feeling utterly exhausted by stress. It is our system’s last line of defence in the face of dreadful threat, but can also be activated by prolonged dwelling in fight/flight.

- And… if we get as far as ‘freeze/collapse’, in order to come back to a state of rest, our system must first re-mobilise and re-experience fight/flight, before returning to rest.

Recognising where we are on the ladder above allows us self-compassion and confidence that our system is doing what it is supposed to do.

Even though the ANS forms only part of the nervous system, for the sake of easy-reading, I will refer to the ANS throughout this blog post as, simply, the nervous system.

Cool fact: 80% of the vagus nerve carries messages from the body to the brain. 20% carries messages from the brain to the body.

Now pause and consider that fact, because it’s fairly mind-blowing.

What does that mean? It means that how relaxed we feel is largely dictated by messages the brain is unconsciously receiving from our body, not the other way round.

Calm the body, calm the mind.

You cannot think yourself to a place of safety. Trying to do will only serve to ramp up your nervous system even more.

What is a regulated nervous system?

The word regulated refers to a nervous system that is able to return to rest and digest after being triggered into either fight/ flight or further into freeze/ collapse. This is learned in childhood and is, ideally, what we want.

Why it’s important: Benefits of a regulated nervous system

Typically, people with a well-regulated nervous system:

- Sleep better

- Are able to relax

- Feel interested in life

- Are able to experience moments of joy, playfulness, spontaneity and excitement

- Approach life with a sense of openness and curiosity

- Are able to fully appreciate the present moment, when bringing awareness to it

- Feel sociable (to a degree that is normal for the individual)

- Feel able to cope with life’s stresses and challenges

- Have a healthier digestive function and immune system

- Have enough energy to see them through day to day life

- Have a better short-term memory

What is normal?

Ideally, we would like to enjoy the benefits of a regulated nervous system, spending most of our time in a state of rest & digest/ safety & social connection. It is normal to move between all three states on a daily or weekly basis, as long as after being triggered, we are able to return to safety & social connection.

This is more difficult for some than others and depends on a number of factors, including how we were responded to in childhood when something triggering happened. Many of us were not taught to regulate and self-sooth (known as vagal toning) by caregivers who either provided comfort and safety or modelled self-soothing.

Another factor is the experience of traumatic events at any time in our lives. Somebody who has not fully processed their body’s response to a traumatic event may experience ongoing trauma and a permanent state of activation or hyper-vigilance.

For many, ‘normal’ is a nervous system stuck in fight/ flight or collapse/ freeze or looping between the two. Perhaps this is where you may be used to being, but is it what you would choose for yourself?

It’s not something we have control over

Scanning for threat is what we have evolved to do. It’s not a conscious process and happens non-stop in the background while we go about our day to day lives. When our nervous system unconsciously detects perceived threat, we experience a stress response and our body is flooded with stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenalin, even if consciously we think we are safe. At the same time, the parts of our brain responsible for processing logic, become compromised. In short – it’s not our fault that we can’t think clearly at those times and our response is not something that we have control over.

Willpower and motivation are useless against a dysregulated nervous system

The good news is that change is possible: we can learn to re-parent our nervous system.

If you suspect that you spend too much time in fight/ flight or freeze/ collapse (or find yourself there very easily), the good news is that awareness and tuning-in can help interrupt old patterns and bring about change. Use the worksheets to start to recognise where your nervous system is at.

As with learning a language or mastering any new skill, the key is to DO the practice. Nothing will change because you have read about the theory. You must do the exercises. Do the practice and learn how to feel what the three states feel like.

Summary

- Survival responses are involuntary and unconscious

- Experiencing all three states on a daily basis or from week to week is normal.

- Someone with a regulated nervous system will be able to return to ventral vagal safety and connection after being triggered.

- For many, being in a constant state of fight/ flight is normal to them.

- Somebody who has experienced a traumatic event and has not fully processed their trauma, may move into fight/flight quickly and from the slightest trigger.

- If we were never taught to self-regulate, we can learn now. It’s not too late.

- To make change happen, practice is essential.

The exercises on the worksheets are credited to (or inspired by) Deb Dana, who adapted Stephen Porges’s Polyvagal Theory for useful practice in the therapeutic setting.

Suggested further reading: Deb Dana: Anchored – How to befriend your nervous system using polyvagal theory